This is Part 4 in a series on tacit knowledge. Read Part 3 here.

We can’t really talk about tacit knowledge today without talking about YouTube.

A couple months ago, Samo Burja wrote an essay on Medium titled The Youtube Revolution in Knowledge Transfer, a piece that I loved and linked to in issue 50 of the Commonplace newsletter. Burja observed the following things:

- First, YouTube is now a thing.

- Second, quality digital cameras have become cheap enough for mass use. This in turn means that everyone can start producing YouTube-worthy content, and have those videos be discoverable, because — hey! — YouTube is now a thing.

- Three, this also means that people with expertise in thing X can now film themselves doing thing X, and clued-in practitioners can watch these experts do thing X and become really good themselves.

- Burja then posits that we’ll see an explosion of tacit skill transfer over the next decade, correlated with the rise of YouTube use, because certain kinds of human expertise may only really be taught through emulation, not through instruction alone.

Burja’s whole essay is great, and I urge you to read it in full.

But there’s a twist here. I linked to Burja’s piece in Issue #50 of my newsletter, which went out on the 24th of September 2019. Burja’s piece was published on the 18th of September. And I’m writing this on the 29th of June the next year. So it’s basically taken me more than nine months before I realised that Burja’s observations may be generalisable — that is, once you realise that YouTube is a great place to learn tacit things, this fact applies to skills far beyond the set of skills Burja talks about in his essay.

In this piece, we’re going to walk through a number of ways you may use YouTube for tacit knowledge acquisition, on a domain-by-domain basis. I’m afraid the anecdotes here are necessarily domain-specific, but the purpose of this piece is to give you certain patterns that you may adapt to whatever skillset you want to acquire in whatever domain you’re interested in.

YouTube use in Judo

Let’s start with Judo.

I'm biased here because I played Judo competitively as a teenager. But Judo is interesting for our purposes because it isn’t a particularly popular sport. In Malaysia, where I’m from, the number of people who play Judo can probably fit into a small football stadium. And the active players — the ones who do Judo regularly — can probably fit into half that. Contrast this population with a sport like badminton, say, or football, or tennis.

What this means is that it is difficult to get good as a judoka in most countries around the world. This fact isn’t limited to Malaysia; in the US, for instance, pretty much every Olympic Judo champion comes from a tiny family-run club called Pedro’s Judo Centre in Wakefield, Massachusetts. Judo isn’t particularly popular outside the club, either. If you find yourself anywhere else in the country: tough luck.

During the worst of the COVID-19 lockdowns earlier this year, Malaysian Judo coach Oon Yeoh began interviewing international Judo players from all over the world, in a series he named Judo In The Time of COVID-19. He wrote, of that experience:

One thing I noticed after interviewing many judo players is that those from very strong judo nations tend not to watch so many judo videos whereas those who come from countries where judo is not so strong, tend to watch a lot of judo videos.

The reason is obvious. If you're from a strong judo nation, there's a lot of institutional support and good coaching, as well as sufficient training partners, training opportunities and competitions. All these combined give you everything you need to develop your skills in judo. But if you live in a place where there's very little judo, you're pretty much left to your own devices. In such circumstances, video is the best resource for you to learn things. (emphasis mine)

Oon first learnt Judo in the US, and was exposed to video-based training from the beginning of his career. (To my knowledge, he remains — to this day — the only Malaysian to have fought in the World Championships). When he says ‘video is the best resource for you to learn things’, we have to be very clear what he means by this.

If you go to YouTube right now and enter a Judo technique, for instance, ‘uchimata’ — you’ll get a results page like so:

The top result is an instructional by US Judo coach Shintaro Higashi:

Higashi’s video on uchimata is particularly good, and instructionals are probably what you’re thinking of when you hear ‘YouTube’ and ‘learning’. But instructionals aren’t the only thing that Oon is talking about.

What Oon is more interested in is analysis of competition footage. I asked him to explain how he used video for this purpose, and he did:

Let's say you want to learn how a particular player does a particular technique. Here are some best practices:

a) Don't just watch just one or two examples of that player doing that technique. Watch multiple examples and try to identify trends or things that that player does in setting up the throw. Take for example, Takato's unique style of ouchi-gari. If you watch enough of them, you'll notice he only does this technique under very specific circumstances (against left-handers who are trying to push his head down). If you notice that, try to understand the reason why.

b) Pay particular attention to grips. How does he grip whenever he wants to do this technique. You will notice a familiar pattern to the gripping. Again, try to understand why.

c) There will be times when the technique fails. Watch those as well and try to understand what went wrong. What was different about this attempt that caused it to fail? Doing this will allow you to isolate the key success factors.

d) Try to look out for variations. Sometimes those differences are very subtle but they are significant. Understanding the variations (when they are used and why the variation are necessary) will give you a better grasp of the technique.

e) It is usually helpful to watch the technique in slow motion. If there is no slow motion replay of the clip available, you may have to download the clip and slow-mo it yourself using a simple video editing program. When I was a student there was no digital videos yet, only VHS cassettes, and I had to use two VCR machines to make slow motion loops of Koga's throws just so I could study them properly!

In a separate interview with US Olympic silver medallist Travis Stevens, Oon asks about video, and Stevens answers:

There is a lot the cadets can do at home to prepare them for future success. Like learning how to break down a fight when watching videos, taking notes on training sessions (emphasis mine), journaling, etc. Winning at judo isn’t just about hard work. There’s a lot more that goes into it than that, like analysis, mental training and so on.

Why study competition footage, and not just instructionals? The answer falls out of everything we’ve explored in our previous posts on tacit knowledge. Expertise is difficult to explicate, and embodied knowledge can only loosely be captured through language. There usually isn't much of an overlap between the greatest practitioners and the greatest teachers in any given domain.

Plus: ask any serious Judo player, and they will tell you that there is also a gap between what is taught in the dojo, and what is used in competition. The charitable explanation here is that the best players can’t explain what they’re doing, because their somatic responses are tied to cues in implicit memory, which makes it impossible for them to notice. The slightly less charitable explanation is that there is a metagame that’s going on at the highest levels of Judo, and the shift in the current meta is kept opaque and available only to those who know how to watch out for it. The completely uncharitable explanation is that Judo is a sport with bad pedagogy, and most people don’t know how to teach it.

(I’m perhaps being a little extreme in that last assessment; but — well, let’s talk about uchimata, shall we? There’s a particularly good video by YouTube user Judo Mat Lab that points out that the throw taught by Higashi, in its form above, is rarely seen in competition. Many top level athletes do something far simpler (they lift the opponent's leg and tilt, not lift their opponent with their hip) — in fact, the tilting form is what is most commonly seen in MMA and in BJJ as well. The funny thing is that when these judokas are asked to demonstrate uchimata, they execute the classical, lifting version first. This is an example of a piece of tacit knowledge that was successfully explicated into a wonderful, comprehensive explanation — but it took a talented YouTuber to do it, and in 2015, 133 years after Judo was first created.)

So the solution here is to do what Oon figured out all those years ago: don’t wait for someone to come along and explain what’s going on. Don’t rely on instructionals alone. Look at actual experts doing the actual thing. In the context of Judo, this means developing the meta-skill of watching competition video yourself, in order to break a competitor’s technique down into its constituent parts. You try to figure out why it’s so effective; later, in the dojo, you attempt to replicate it by copying.

In fact, as we’ll soon see: this principle is generalisable. When you want to learn a skill on YouTube, you should spend a little bit of time watching instructionals, but then spend the rest of it watching experts doing the actual thing. The former is by definition explicit; the latter allows you to capture what is tacit.

Programming

Let’s move on to programming, which is probably more relevant to the topic of careers.

When I started programming in university in 2009, there was already a fair amount of programming content on the web. This period coincided with the rise of the MOOC, and so the number of lectures about programming that were freely available went way up in the span of a few years.

I really appreciated this trend. I remember thinking that anyone could watch the legendary Harold Abelson explain the basics of computer programming at MIT; they could catch Sal Khan teaching math on Khan Academy, and of course they were spoilt for choice by the programming conference talks that conf organisers were beginning to upload, en masse, to YouTube. I was a poor student at the time; I remember thinking that it was absolutely great that I could get all of this in piped to me in my dorm room in Singapore; I felt like one of the luckiest people alive.

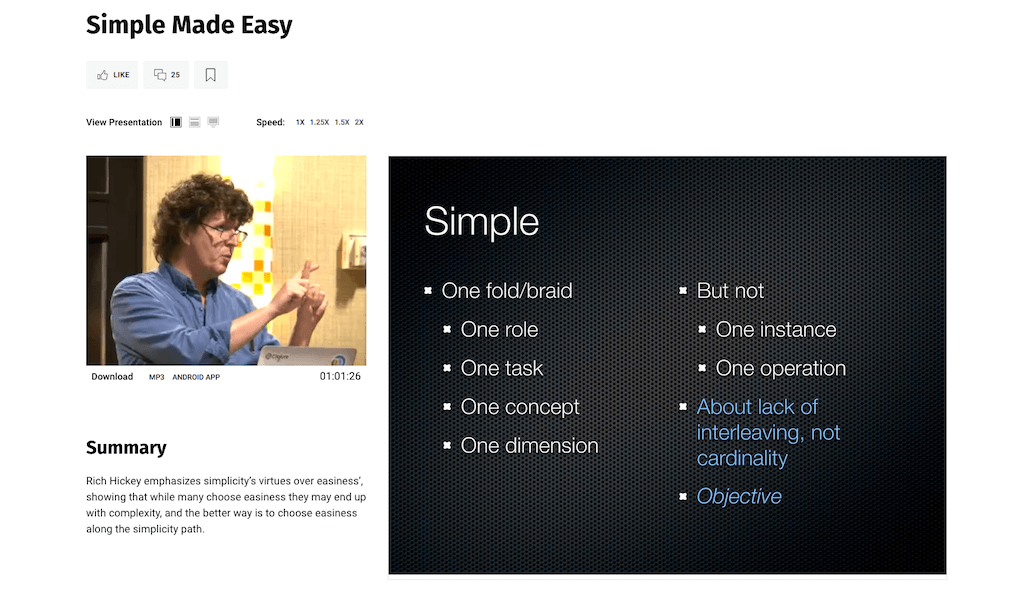

But talks and lectures are basically instructionals. They are necessarily explicit. Even when speakers attempt to express some deep, tacit principle, the information they can communicate is limited by the nature of human language itself. I remember watching Rich Hickey’s famous talk Simple Made Easy and thinking to myself: “wow, this seems profound, this seems really important” and having zero way to use it in my daily practice of programming.

At this point in the series, we know why it is difficult to apply Hickey’s ideas in Simple Made Easy — more importantly, we have the language to talk about it. We know that Hickey’s knowledge is relational tacit knowledge; we also know that Hickey’s expertise is made up of prototypes in his implicit memory, and that the only way to get at it is to build up a library of equivalent prototypes in our heads. And that's not all: we must also acquire the solutions that Hickey matches to those prototypes, when he’s building these large, complicated systems. In simpler terms, the only way to truly internalise ‘Simple Made Easy’ is to program under Hickey’s guidance for a bit.

In fact, there’s a good rule of thumb here that I think is worth keeping in mind: if something can fit into the length of a typical programming conference talk, the odds are good that the aforementioned thing is easily explicable. You get the sense that Hickey’s talk could not fit into the length of a conference keynote; if you gave him more time, he could go on.

You get this feeling because Hickey is trying to communicate something deeply tacit: a principle that he has imbued into all the projects he’s worked on from Clojure to Datomic. And indeed, the more common programming conf talks tend not be like Hickey’s; they tend to be about easily explicable topics like ‘how to use cool new feature in programming language X’ or ‘how to do technique Z in framework Y’; you’re not likely to get higher level things like “how do I structure a program to thread the thin line between too much abstraction and too little?” or “how do I evaluate the risks of my client being an idiot, which means we’ll have to redesign a whole subsystem a month from now?” That sort of thing is tacit, you pick it up while on the job, working alongside more experienced people.

So if conference talks and lectures are the programming equivalent of Judo instructionals, what is the equivalent of analysing competition videos? The answer, of course, is coding livestreams.

I think coding livestreams really only became a thing within the last five years or so — perhaps due to the growth and influence of gaming streamers on Twitch. It’s sort of crept up on the programming world — I certainly wasn’t aware of its usefulness when I read Burja’s piece last year. But I think we are all the better for it now that it’s here.

Watching someone program is a very different experience when compared to watching a conference keynote, or even an instructional. It is the closest experience you can get to watching a senior developer code next to you, or having them pair program alongside you. In fact, in some ways, livestreams are more useful because you can go back and rewatch certain segments; once those streams are uploaded to YouTube, they also become more scalable than a one-on-one pair programming session.

I think it’s pretty obvious to programmers that there are certain things you can only pick up when you’re watching other programmers in action that you cannot when they’re giving talks about their work. The most obvious example of this is perhaps their debugging ability — in the video I linked to above, you can watch when Tsoding encounters little things that don’t go according to plan, and then listen to him reason his way out of it. This tells you something about the model of the problem domain he has inside his head.

Personally, I find it really interesting to watch more experienced programmers structure a program over time. At the beginning of a project, it’s usually not clear what the shape of the problem is, and so the first program structure that a programmer picks tends not to be the best. What I tend to watch out for is the exact point at which a programmer decides they have to restructure a certain subcomponent — I ask things like: how did they know to pick a new structure? If it was a ‘feeling’, what feeling was it that they’re picking up on? What cues or ‘smells’ did they notice? Would I have done something differently? And could I attempt to copy their solution instead?

Music

Singer songwriter John Mayer streamed a guitar lesson on Instagram Live on May 7th, earlier this year. At 8:35 in the video, he segued to a lesson about the nature of skill progression in guitar that I thought was pretty profound:

I quote:

“The idea, that you already know how to play the guitar — if you learn the pentatonic, if you’ve played along to blues records and rock records, and you’ve soloed for awhile, you have all the moving parts.

What we’re all learning how to do is … to do THAT, THEN. So you know all the letters in the alphabet, they’re really easy to learn on the guitar — that’s the minute to learn. And the lifetime to master part is: how do you implement it and how you think?

At a certain point, all learning guitar from records is, ‘oh you can do that then!’ So you’re not learning how to play that type of thing, you’re learning you can play that thing at that point in time.”

If you shove what Mayer is saying into the models we’ve explored over the course of this series, you should immediately grok what Mayer is saying. He’s saying that guitar playing is roughly two levels of progression: the first is to learn the basics of guitar playing — the pentatonic scale, and all the embodied knowledge necessary to execute various types of guitar picks. But the level above is essentially the process of expanding the set of prototypes in your head. You want to know what’s good in the genres you’re interested in, you want to know what’s been tried before, and you want to know — as Mayer puts it — ‘that you can do that then’.

So what better way to acquire this knowledge than to listen to lots and lots of music? And what better way to learn technique than to watch lots of guitar-playing videos on the web?

Wrapping Up

I think there are two trends that make up the ‘YouTube revolution in knowledge transfer’, as Burja puts it. We’ve seen both of them in every domain we’ve explored, above.

- The first thing is an increased level of access to quality instructionals. Higashi’s video, Abelson’s lecture, and Mayer’s Instagram story are levels above what you can get if you attended the average meetup in your area.

- The second thing is that YouTube greatly expands the set of people who can watch expert practitioners doing their thing. As we’ve seen from Oon’s example: when you have the opportunity, bias towards watching experts doing the actual thing. Instructional videos are often limited by the quality of the instructors you have in your field.

In fact, I haven’t tried this yet, but I want to know if Oon Yeoh’s principles for analysing Judo video generalises to every other domain of tacit knowledge. If we take his list and remove the Judo-specific references, we get:

- Don’t just watch one or two examples of the expert doing a technique. Gather multiple examples and try to identify trends or commonalities in the usage of their technique. When you notice such commonalities, try and understand why those commonalities exist.

- Pay particular attention to context. What happens before or after application of the technique?

- There will be times when the technique fails. Watch those as well and try to understand what went wrong.

- Try and look out for variations. These variations represent changes in the action script associated with the prototype in the expert’s head. Sometimes these differences are very subtle, but they are significant. Understanding the variations will give you a better grasp of the technique.

- It is usually helpful to watch the technique in slow motion. Download the clip and slo-mo it yourself using a free video editing program.

To be fair, Judo is an incredibly technical sport, and it might be overkill to use techniques adapted for that domain. But even if you don’t use Oon’s sophisticated techniques, you might still be pleasantly surprised by the benefits of watching experts doing actual things anyway. Sometimes your brain just picks up on tacit knowledge the natural way: that is, by osmosis.

As Patrick McKenzie observed:

I got about ~40% faster solving sudoku after casually watching an hour of YouTube (turns out sudoku YouTube is a thing) and now I’m wondering how many other things in life are shaped like this.

— Patrick McKenzie (@patio11) May 25, 2020

And perhaps this shouldn’t surprise us — after all, blind copying is how we were originally made to learn.

Read Part 5 — An Easier Method to Extract Tacit Knowledge

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Expertise Acceleration topic cluster. Read more from this topic here→